This post describes, my recovery from the loss of my wife to a degenerative neurological condition called Huntington’s Disease. She was healed of this condition when she went to live with our Heavenly Father at 2:30AM, the 10th of January 2021. You can read the announcement here.

Or if you would like to read our story from the beginning, you can start with: How We Got Here…

This week is something of a landmark or dividing line. This Sunday is the last one where Jean and I will be in church as individuals. By the next time we gather with the rest of our little fellowship, we will have undergone an amazing transformation to become simply “The Porter Family.”

For that reason (and many, many others), it seems appropriate to us to begin recapping the past three or four months and consider some of the steps that we have gone through in the process of recovery – and highlight what is still left to be done. You see, remarriage is, for us, a wonderful milestone, but if you think about it, a milestone is just a marker on the road you are traveling. And your road will likely be different from ours, it may pass that same marker, or you may find yourself soon standing before a different one perhaps labeled, “Start Second Career” or something else. Literally, God only knows.

And speaking of roads being traveled, this week Jean and I will be on a post-nuptial road trip visiting family. Consequently, next Sunday we will not be posting, however we will be back June 13th.

❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦

A recurring theme in many posts that we read on support forums – as well as life in general – concerns loneliness and the avoidance thereof. And there are good reasons for this concern to be so ubiquitous. For example, it is often the first symptom that the caregiver experiences personally as they stand by powerlessly while dementia begins to slowly eat away at the person they love.

This situation is an example of a condition called “Ambiguous Loss” – which includes the cruelly painful process of mourning the passing of someone whom you love, but who is still physically present. In fact, one of the things that God used to bring us (Jean Barnes and Michael Porter) together was the shared memories of navigating those terrible waters. Waters filled with horrifying icebergs in the form of doubts and questions about who we were and where we were really going.

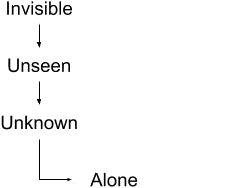

While we survived that period of our lives, it certainly wasn’t pleasant. One of the keys to that survival was learning to draw a distinction between two very different, yet confusingly similar, ideas. What we are speaking of is the difference between being by yourself, and being alone. We have learned that drawing a clear, unambiguous distinction between the two is critical because when one is caring for someone else, one of them is just part of your daily routine, while the other is an illness that must be eradicated to the greatest extent possible.

To see what we mean, consider that being alone and isolated is normal and even to be expected when caregiving – especially in the midst of the current Covid-19 panic. However, aloneness is not inherently a problem. Many people enjoy hiking, climbing, fishing, hunting or other solo pursuits out in nature. And despite being the only human being in miles, they nevertheless report a deep sense of connectedness to God, nature, the universe, etc.

Being alone, on the other hand, implies a feeling of being disconnected from what is going on around you, of being dissociated from everything beyond the confines of your own skin. Hence, someone can feel very alone even in a crowded room. Quite rightly, the medical profession has identified this kind of dissociation as a pathology.

Unfortunately, this quote illustrates for us that dissociation is a pathology that society pushes relentlessly in nearly every realm of life – at times bordering on psychosis in the destruction of reality in favor of an oxymoronic “personal reality” or “individual truth.”

But getting back to caregivers, we have suffered through many things in common over the course of our separate caregiving journeys, but there are always many unique aspects, as well, so we’ll speak separately for a bit…

Michael:

A problem that I think is probably specific to men is that we tend to (as my sister once described it) put all our eggs in one basket. Or to put it another way, we tend to concentrate much of our attention on just one person: our wife. Consequently, when she begins to exhibit the signs of dementia, we tend to become lost very quickly.

For myself, this issue was particularly troublesome because my Janet was always the disciplined, logical one – then, seemingly overnight, it was just all gone. I remember thinking that my life felt like the rope to my anchor had been suddenly cut and I was adrift with no solid point of reference that I could guide on. During that time, I remember feeling like one of us was going insane, but which one was it? Looking back, I am amazed at how willing I was to throw myself under the bus to maintain the image of Janet that I had in my head.

I was totally unprepared to deal with the anger, irrational behavior, and violent outbursts. I had no idea, at first, what I should do. I remember crying out, “Why can’t I have Janet back for just five minutes so she can tell me what to do?” But that never happened.

In the end the image became unmaintainable and I had to come to grips with the objective fact that Janet, as I had always known her, was gone. And even more horrifying was the possibility that the person that I thought she had been, never really existed – that the “personality quirks” I had always recognized were not the legacy of an abusive childhood that could eventually heal, but symptoms of a disease that would only get worse.

There is no isolation so profound as the one produced when the person being missed is still present physically but is absent in every other possible way.

Jean:

If you had parked outside my house any time during 1987, you would notice a nightly routine. Our two children would be off to bed by 9:30 and their bedroom lights would go off. Soon the living room and master bedroom would go dark as we all went to sleep. Then about 30 minutes later, the living room lamp would come on. It was me. I was reading again every brochure we had accumulated about the relatively unknown condition called Huntington’s Disease. I would spend an hour or so reading and crying, begging the Lord to please not let us have to deal with HD.

My husband’s grandmother had died of HD a year before we married. Now Don’s dad was in late stages of the disease. A few months later we buried his dad in Indiana, and to my horror, I began seeing early signs in my husband. Don’s health continued deteriorating and in 2006, we laid him to rest. We had been married almost 35 years and I felt much loneliness. My identity as a wife and helpmeet to my husband disappeared. Then, just seven weeks after my husband died, his older sister also died in her sleep, of HD.

God gave us comfort and I felt surely my children would escape HD. My son seemed healthy, but then I began seeing signs of HD in my precious daughter. Jennifer was an accomplished church pianist and loved using her talents to serve the Lord. She and her husband had two precious sons that they had adopted.

About this time, her husband forced her out of the house to make room for another woman. Jennifer came to live with me. One of my greatest joys in life was taking care of her during her last years of life, even though every day was totally exhausting. In Feb. 2021, God called her home very unexpectedly. I knew she was getting weaker but surely did not expect her to die that day. The following days were a blur of wondering why I was even alive, and what my purpose in life was now? HD had now taken two of my immediate family – and five altogether.

So with these problems and experiences, what did we do? Well, ultimately we both came to see that our salvation lay, not in trying to avoid reality, but in fully embracing it. You see, no matter how difficult it might be, reality is – well, real. So in that sense, there is really no alternative – except perhaps a path resulting in extreme detachment or perhaps even psychosis.

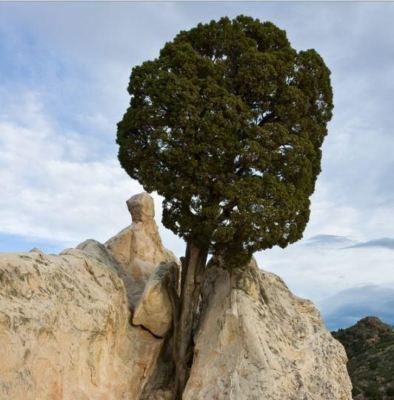

But accepting reality means accepting all of what is real – not just the parts that we like or are ready to accept. For example, you might like the happy pleasurable parts of life but want to reject the messy bits, or you might find joy in creation while feeling uncomfortable with the idea of a Creator. Likewise, a common meme shows a tree growing up through a split that it has created in a large rock.

The picture’s intended lesson is about persistence and asks us to concentrate on the tree. But the rock also exists, and the picture shows the result of decades or even centuries of “contention” between rock and tree. While things look good for the tree right now, the final result is still far from certain. After all, a forest fire could still come through and destroy the tree while leaving the rock unscathed.

Perhaps a better lesson is that from the human perspective, reality is seldom a flash of life-changing enlightenment. Rather, for created beings such as ourselves, reality is always being revealed as a curious mixture of “is” and “is becoming,” where we can never be absolutely sure of all the final details. However, that uncertainty doesn’t mean that we are adrift with no solid point of reference.

To the contrary, verbs often imply nouns. For example, our existence as created beings implies the existence of a Creator. And the existence of blessings is a sign that the Creator cares about His creation. A point that brings us back to this post’s original assertion: You don’t have to be alone.

Even when times are at their darkest, you will discover that, if you look for it, there is always enough light to illuminate at least your next step. Our Creator has known for as long as there have been human beings, that it is not good for them to be alone.

So He is always there, and oftentimes He brings into our lives other people to accompany us and support us on our journey – sometimes as a friend, sometimes as a sibling, and sometimes as a spouse.

In Christ, Amen ☩

❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦

A prayer for when you are feeling alone and disconnected…

“Blessed are You, Lord God, King of the Universe. It is right that I should at all times and in all circumstances bless You for the light and warmth that You bring to our world. But today I want to bless You especially for those loving souls that You call together to surround us with comfort in our pain. Please show me how to be such a person to others. Amen.”