This post describes, my recovery from the loss of my wife to a degenerative neurological condition called Huntington’s Disease. She was healed of this condition when she went to live with our Heavenly Father at 2:30AM, the 10th of January 2021. You can read the announcement here.

Or if you would like to read our story from the beginning, you can start with: How We Got Here…

This week we’ll continue the process of revisiting some of my posts written over the past year and a half, and giving them a bit of a facelift.

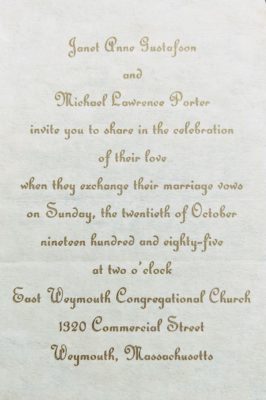

This week Jean went through the past posts and identified one that she felt was one of her favorites. It originally ran July 12th of 2020, and was entitled What is Success? The post is notable to me for being the first post for which Jean left me a comment:

“Oh, I sure needed this today! I want to save it and come back frequently to remind myself of these things, even though this is my 2nd HD marathon.

“Thank you, Michael, for your wisdom and faith, and for sharing your thoughts so eloquently!”

At the time, she was caring for her daughter (Jennifer), after already having lost her husband several years before. For me, the comment documents the day that I first became aware that a person named Jean Barnes existed. But concerning the future… I had no idea…

❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦

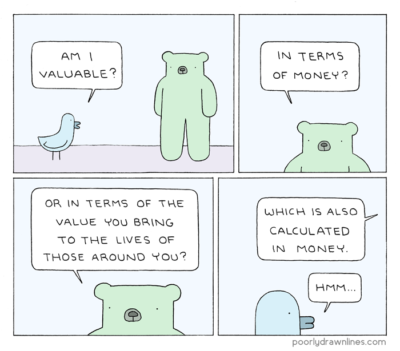

A past post talked about what happens to caregivers after they have successfully completed their care mission, and how they can find fulfillment and meaning by contributing back to the community. However, whether you realized it or not, there was a rather glaring hole in that discussion, which I intend to close right now. The previous post just assumes that the caregiver’s work ended in success.

However, that assumption begs the question, “In the context of caring for someone with an illness where the patient always dies, what exactly does success mean?”

- Kept them safe.

- Kept them alive as long as medically possible.

- Gave them “Death with Dignity”.

- Helped them to be happy.

- Did the best I could.

- Kept them out of a long-term care facility.

- Got them admitted to a long-term care facility.

- I outlived the person for whom I was caring.

But which, if any, of these goals forms a good basis for determining success or failure as a caregiver? Before we try to answer that specific query, let’s take a little broader perspective on the matter by considering a common metaphor: The foot race.

Over the centuries, the foot race has repeatedly proven itself as a way of explaining, exploring, and describing the meaning of success. For example, how many times have you heard someone describe caregiving as a “marathon” and not a “sprint?” How many times have you said something like that yourself?

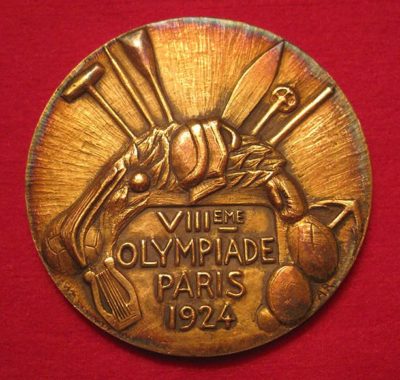

The reason for this popularity should be obvious. A foot race has a clearly defined beginning when the starting pistol goes off, a predetermined length, and a precise end when the runner breaks the tape at the finish line. In addition, a race often includes the promise of a reward for winning, ranging from congratulatory handshakes and hugs, to formal awards such as this gold medal from the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, France. (Why the 1924 Paris Olympics? Patience, dear friends, patience.)

The problem, of course, is that the marathon a caregiver runs lacks nearly all of the things that make a race an attractive metaphor. For example, when did the cognitive problems definitively start? Maybe your loved one had been feeling the effects for decades before recognizing them. And predetermined length? Who are we kidding? They may survive for months, years or even decades.

Despite all these difficulties, race analogies can nevertheless be helpful by bringing with them a certain intuitive understanding of the situation. But this metaphor has much more to offer than mere vague generalizations, a point demonstrated by a wonderful movie I saw many years ago.

The year was 1981 and the Academy Award winner for best picture was a historical drama surrounding the eighth modern Olympiad, held in Paris in 1924. The movie is, of course, the magnificent Chariots of Fire, focusing on the lives of Eric Liddell – the so-called “Flying Scotsman” – and Harold Abrahams. You soon discover, through the film, that in many ways, these two men could not have been more different. Given their differences, it would be tempting (and easy) to cast comparison between the two of them in terms of the good (Liddell) and bad (Abrahams), but the truth is far too complex for that simplistic of a structure.

For example, while it is true that Abrahams was at times arrogant, carrying a chip on his shoulder the size of Big Ben, those personality quirks were not without cause. After all, Abrahams was Jewish, and England at the time was rife with antisemitism. But there was more to the man than that. He also demonstrated the ability to love deeply, and had a reputation for being intensely loyal to friends, his teammates, and (despite the racial problems) his country.

The really interesting difference between the two men is their reasons for running, why they raced. Liddell ran as an expression of who he was as a human being. As he once told his sister, “I believe God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast! And when I run, I feel His pleasure.” Liddell raced because it gave him a reason to run and express who he was. A hallmark of the pleasure he felt was apparent in his unique running style. As can be seen in archival films from the time, when he crossed the finish line, his arms would be flailing, his head would be thrown back and his mouth would be gaping open in an impossibly wide smile – a smile.

By contrast, due to the daily reality that he lived, Abrahams had very different reasons for racing. He once told a friend that his intent for the antisemitic mob was to “…run them into the ground!” Simply running a good race was not adequate: all that mattered to him was winning. He wanted to be able to taunt them and rub their noses in his success. For him, there was no joy in running, only anger and revenge. But then something, we don’t know exactly what, changed him.

Perhaps it was the realization that winning an Olympic gold medal didn’t feel nearly as good as he thought it would, but instead left him feeling hollow inside. Maybe, as in the film, he witnessed Liddell win his gold medal event and saw on his face another reason to compete – the sheer joy of it. Conceivably, it was something that God worked out silently in the privacy of his heart. One thing is clear: if you read about his life after 1924 and all the things he did publicly and privately, he was a different person.

So what does all this talk have to do with being a successful caregiver? Simply this: I would humbly submit that there are two approaches to caregiving, that mirror the approaches these two men exhibited when racing. Moreover, I contend that we aren’t stuck in one modus operandi. Rather, people can and do change their approaches to the task of caregiving all the time – in other words, we have good days and we have bad days.

So the first approach is analogous to how a younger Abrahams approached running. Here the caregiver sees themselves as being embroiled in a battle, not against antisemitism or bigotry, but a disease. This approach does work, for a while at least. For example, Abrahams’ single-minded focus on winning at all costs, did get him to the Olympics, and it won him a gold medal. But the price was a level of isolated exertion that was ultimately unsustainable. Perhaps this is why so many caregivers die before the person they are caring for does: caregiving as a battle, in the long term, doesn’t work.

As I said before, the problem is that with our race, the beginning is uncertain, the duration is unknown and the end is unpredictable. So what we need is an approach that is more like the way Liddell ran a race, an approach that focuses less on what we are “doing” and more on who we “are.” With such an approach, success or failure won’t be judged at some arbitrary point in the future when the race is done. Rather, the goal is to express who you are and your giftedness right now, today, with every step.

What parent doesn’t find pleasure in seeing their child using and enjoying a special gift they gave them? Yet too often people of faith fail to recognize that God feels pleasure when we make full use of the gifts He has provided us. Like Liddell all those years ago, we can affirm that “…when I run (care/write/program/love my spouse/etc.), I feel His pleasure.” Moreover, we can learn that His pleasure isn’t just a nice feeling that lasts for a moment and then is gone. Rather, we can experience His pleasure as a sustaining force that enlivens us, strengthens us, and lifts us up on the wings of eagles.

Now that, my friends, is success.

In Christ, Amen ☩

❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦

A prayer for when you are feeling spent…

“Blessed are You, Lord God, King of the Universe. It is right that I should at all times and in all circumstances bless You for the gifts that you bestow. But today I want to bless You especially for the strength that You give me for today. So often I feel run down and run over. Thank You for not just enabling me to survive trials, but to thrive in the face of adversity. Show me how to feel Your pleasure. Amen.”