This post describes, in part, the effects of a degenerative neurological condition called Huntington’s Disease. Any negative behavior on the part of my wife should be attributed to that condition. Any negative behavior on the part of myself should be attributed to my need for God’s ongoing grace.

If you would like to read our story from the beginning, you can start here: How We Got Here…

This week Janet seems to be going through cycles where one moment she wants to be left alone, but the next, she wants to be involved in conversations and decisions. In fact, Frannie is experiencing increasing upset over Janet’s “eavesdropping” on conversations and then trying to participate in them – even when it’s clear that she didn’t really understand what she heard. I seem to be back in the mode of getting between the two of them to prevent verbal altercations.

Another thing I have talked about in the past, that bothers Frannie greatly, is Janet’s refusal to use her walker. I have come to realize that short of tying her down, there really is no way, as a practical matter, to stop her from getting up and toddling around the apartment. It strikes me that perhaps refusing to use the walker is her last act of rebellion.

Come to think of it, that word pretty well sums up Janet’s life: “rebellion.” Whether spiritually, politically, educationally or any other way you can name, Janet has always seemed to have her BS detector (on a scale of 1 to 10) hardwired on 11. She has left churches over misbehavior of clergy. Over two election cycles, she worked tirelessly for Perot. Even in her current diminished cognitive state, she still talks about his prescience in seeing where previous administrations were taking the country.

I have written before about how, when she was teaching in public schools, she tailored lessons for individual students. But she also cared about the small stuff. For example, Janet is from Massachusetts and for those of you who have never been there, yes, they do talk funny. But Janet was always careful to model correct pronunciation. In fact, one of the ways I could tell she was ill was if, in response to the question, “How are you feeling?” she would say “mediocah” (mediocre).

But Janet was always a rebel with a cause. She never believed in tearing things down simply for the pleasure of seeing others fail. For her, there was always a reason for her rebellion: to make the world a better place.

❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦

The post last week talked about what happens to caregivers after they have successfully completed their care mission, and how they can find fulfillment and meaning by contributing back to the community. However, whether you realized it or not, there was a rather glaring hole in that discussion, which I intend to close right now. The previous post just assumes that the caregiver’s work ended in success. However, in the context of caring for someone with a terminal illness where the patient always dies, what exactly does success mean?

- Kept them safe.

- Kept them alive as long as medically possible.

- Gave them “Death with Dignity”.

- Helped them to be happy.

- Did the best I could.

- Kept them out of a long-term care facility.

- Got them admitted to a long-term care facility.

- I outlived the person for whom I was caring.

But which, if any, of these goals forms a good basis for determining success or failure as a caregiver for someone with a terminal illness? Before we try to answer that specific query, let’s take a little broader perspective on the matter by considering a common metaphor: The foot race.

Over the centuries, the foot race has repeatedly proven itself as a way of explaining, exploring, and describing the meaning of success. For example, how many times have you heard someone describe caregiving as a “marathon” and not a “sprint?” How many times have you said something like that yourself?

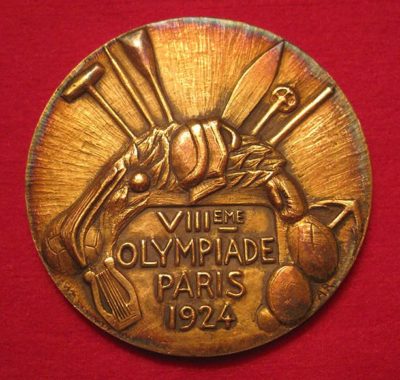

The reason for this popularity should be obvious. Consider: a foot race has a clearly defined beginning (the starting pistol goes off), a predetermined length, a precise end (when the runner breaks the tape at the finish line), and a reward for winning, ranging from congratulatory handshakes and hugs, to formal awards such as this gold medal from the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, France. (Why the 1924 Paris Olympics? Patience, dear friends, patience.)

Despite all these difficulties, race analogies can nevertheless be helpful by bringing with them a certain intuitive understanding of the situation. But this metaphor has much more to offer than mere vague generalizations. A point demonstrated by a wonderful movie I saw many years ago.

The year was 1981 and the Academy Award winner for best picture was a historical drama surrounding the eighth modern Olympiad, held in Paris in 1924. The movie is, of course, the magnificent Chariots of Fire. Focusing on the lives of Eric Liddell – the so-called “Flying Scotsman” – and Harold Abrahams, you soon discover through the film that in many ways, these two men could not have been more different. Given their differences, it would be tempting (and easy) to cast comparison between the two of them in terms of the good (Liddell) and bad (Abrahams), but the truth is far too complex for that simplistic of a structure.

For example, while it is true that Abrahams was at times arrogant, carrying a chip on his shoulder the size of Big Ben, those personality quirks were not without cause. After all, Abrahams was Jewish, and England at the time was rife with antisemitism. But there was more to the man than that. He also demonstrated the ability to love deeply, and had a reputation for being intensely loyal to friends, his teammates, and his country.

The really interesting difference between the two men is their reasons for running, why they raced. Liddell ran as an expression of who he was as a human being. As he once told his sister, “I believe God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast! And when I run, I feel His pleasure.” Liddell raced because it gave him a reason to run and express who he was. A hallmark of the pleasure he felt was apparent in his unique running style. As can be seen in archival films from the time, when he crossed the finish line, his arms would be flailing, his head would be thrown back and his mouth would be gaping open in an impossibly wide smile – a smile.

By contrast, due to the daily reality he lived, Abrahams had a very different reason for racing. He once told a friend that his intent for the antisemitic mob was to “…run them into the ground!” Simply running a good race was not adequate: all that mattered to him was winning. He wanted to be able to rub their noses in his success. For him, there was no joy in running, only anger and revenge. But then something, we don’t know exactly what, changed him.

Perhaps it was the realization that winning an Olympic gold medal didn’t feel nearly as good as he thought it would, but instead left him feeling hollow inside. Maybe, as in the film, he witnessed Liddell win his gold medal event and saw on his face another reason to compete – the sheer joy of it. Conceivably, it was something that God worked out silently in the privacy of his heart. One thing is clear: if you read about his life after 1924 and all the things he did publicly and privately, he was a different person.

So what does all this talk have to do with being a successful caregiver? Simply this: I would humbly submit that there are two approaches to caregiving, that mirror the approaches these two men exhibited when racing. Moreover, I contend that we aren’t stuck in one modus operandi. Rather, people can and do change their approaches to the task of caregiving all the time – in other words, we have good days and we have bad days.

So the first approach is analogous to how a younger Abrahams approached running. Here the caregiver sees themselves as being embroiled in a battle, not against antisemitism or bigotry, but a disease. This approach does work, for a while at least. For example, Abrahams’ single-minded focus on winning at all costs, did get him to the Olympics, and it won him a gold medal. But it called for a level of isolated exertion that was ultimately unsustainable. Perhaps this is why so many caregivers die before the person they are caring for does: caregiving as a battle, in the long term, doesn’t work.

As I said before, the problem is that with our race, the beginning is uncertain, the duration is unknown and the end is unpredictable. So what we need is an approach that is more like the way Liddell ran a race. An approach that focuses less on what we are “doing” and more on who we “are.” With such an approach, success or failure isn’t judged at some arbitrary point in the future when the race is done. Rather, the goal is to express who you are and your giftedness right now, today, with every step.

What parent doesn’t find pleasure in seeing their child using and enjoying a special gift they gave them? Yet too often people of faith fail to recognize that God feels pleasure when we make full use of the gifts He has provided us. Like Liddell all those years ago, we can affirm that “…when I run (care/write/program/etc.), I feel His pleasure.” Moreover, we can learn that His pleasure isn’t just a nice feeling that lasts for a moment and then is gone. Rather, we can experience His pleasure as a sustaining force that enlivens us, strengthens us, and lifts us up on the wings of eagles.

Now that, my friends, is success.

In Christ, Amen ☩

❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦ ❦

A prayer for when you are feeling spent…

“Blessed are You, Lord God, King of the Universe. It is right that I should at all times and in all circumstances bless You for the gifts that you bestow. But today I want to bless You especially for the strength that You give me for today. So often I feel run down and run over. Thank you for not just enabling me to survive trials, but to thrive in the face of adversity. Show me how to feel Your pleasure. Amen”